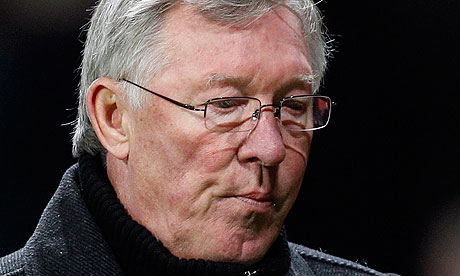

It was not the best of starts. The first match, a quarter of a century ago, was a 2-0 defeat on a bumpy pitch at Oxford United. In the dressing room, Alex Ferguson was finding it hard to disguise his nerves.

"I can remember him naming the team," Peter Davenport says. "He went through the defence and midfield and said: 'Right, up front, Frank and Nigel. OK lads?' There was a pause, then Robbo said: 'Nigel? Who's Nigel?' Fergie points at me and goes: 'Him, Nigel Davenport.' He'd got me confused with the actor from Howards' Way."

What has happened over the following 25 years identifies Ferguson as a man of phenomenal staying power and consistency. Sir Matt Busby was 62 when he closed his reign at Manchester United. Brian Clough left the game at 58. At Liverpool, Bob Paisley lasted until 64. Bill Shankly was 60. Nobody has managed longer than Ferguson at the highest level. Or with greater competitive courage. Never has a manager been so relentless in his ambition and so deeply embedded in the business of winning football matches and forming history.

He turns 70 next month and the mind goes back to 2003, when Sir Bobby Robson reached that age. Ferguson sat behind his desk at United's training ground and blew out his cheeks in disbelief. He was asked whether he could see himself going on so long and his response was delivered like a slap. "No bloody chance."

It has been an epic run. The 25th anniversary arrives on Sunday, and still there is no sign of the system getting the better of him. Retirement, Ferguson once said, is for other people. As long as he has his health, he says, he will continue to work, and he cites the cancer diagnosis of his father, Alexander, within a week of retiring from the Fairfields shipyard in Govan. "There are too many examples of people who retire and are in their box soon after. Because you're taking away the very thing that makes you alive."

But there will come a time when Ferguson has to cut himself free. Retirement isn't something he can file away in a drawer and when it comes to the lessons of history, the Busby handover and the ordeals of the men who replaced him, the critical question is how Ferguson will make his retreat and whether the club can manage the loss without repeating the mistakes made before.

Wilf McGuinness inherited the team from Busby in 1969 and, by his own admission, was never fully accepted by the senior players. Probably because he was not Busby. Now 74, his affection for United still shines brightly but he, better than anybody, understands how difficult it can be to replace the man behind an empire.

"Did I feel I had the full respect of all the players all the time?" he says. "Sadly, the honest answer has to be 'not really'."

He lasted eight months before Busby reappointed himself as manager. Or "four seasons", as McGuinness prefers to describe it: "Summer, autumn, winter and spring – and summer was the most successful."

McGuinness recalls it as "a supremely harrowing period". A mutinous one, too. McGuinness dropped Bobby Charlton and Denis Law and tried to assert some authority. One player went to the Sunday Times with his grievances, complaining on condition of anonymity that Busby's replacement was so bad at his job he would waste £1m if he were given it to spend. The transfer record at the time was £165,000.

It may be that the manager second in line to Ferguson has the more desirable job. The first man in will have to possess unbreakable self-belief, if such a man exists. Every trophy, every memorable achievement, every European campaign will be set against his predecessor's record. Every defeat will be accompanied by sniping that he is not a patch on the last man.

"You're going to need someone very experienced," Ferguson says. "It's not going to be a job for a young manager."

David Gill, the United chief executive, will be in charge of the process, though he says Ferguson will be prominently involved. "It would be a collective body, not a big body, but we would get all the input to make sure we make the appropriate choice. There won't be meltdown. It will clearly be a sea change for the club and we have to be ready."

But United made similar noises in 2002, when Ferguson was supposed to retire, and the man they chose, Sven-Goran Eriksson, is now regarded at Old Trafford as a dodged bullet. Since Eriksson took the call to inform him Ferguson had changed his mind, he has closed out his time with England then hopped between jobs with Manchester City (11 months), Mexico (10 months), Notts County (seven months), Ivory Coast (three months) and Leicester City (12 months). Six jobs on three continents, five of them since 2006.

José Mourinho is the name at the top of every betting-shop board, ahead of Pep Guardiola and David Moyes third, but for now all that can be said with certainty is that whoever comes in will be spared some of the issues that faced Ferguson when he replaced Ron Atkinson in 1986.

Atkinson had let his team grow old, whereas Ferguson has unselfishly hoarded players who may not reach their potential until well after he is gone. His goalkeeper, David de Gea, could be at Old Trafford for a decade. Ditto a back four of Rafael da Silva, Phil Jones, Chris Smalling and Fábio da Silva. "These young players are the future of Manchester United," Ferguson says, and there is a stark contrast to be drawn with the club he found 25 years ago.

One of Ferguson's first instructions to United's board was to start clearing out the older players and replace them with younger versions. A friend asked Ferguson what he made of the youth policy Atkinson had left behind. "What youth policy?" he replied. "He's left me a shower of shit."

Frank O'Farrell also inherited an ageing team. He took over from Busby in 1971 and lasted 81 matches. He reflects on it being "a bit like following Lord Olivier on stage".

O'Farrell, like McGuinness, ran into problems with the older, more established players. "I once made Denis Law substitute and he didn't want to sit on the bench to watch the game," he says. "He wanted to stay in the dressing room."

In the words of McGuinness, Busby was "the perfect role model for any aspiring manager, but an extremely difficult act to follow. Matt had so much knowledge, but he was also an immensely mature character with that wonderful deep voice. He had a certain aura, a magnetic presence which exuded calmness and reassurance. In contrast, I was not particularly mature and my voice was not remarkable in any way, except for being loud."

O'Farrell has just put his memories into a book that will make hard reading for anyone who considers Busby to be flawless of character. All Change at Old Trafford depicts Busby as a man who could not let go.

"When I arrived, Matt was still in the manager's office and there were workmen constructing a new small office for the new manager – me – down the corridor," O'Farrell, who is now 84, says. "The alarm bells started ringing. Matt was not manager any more, but he was still going to keep the office."

Busby had taken on the role of "junior director" but, according to O'Farrell, he interfered with team matters to the point where he became "a hindrance". Busby had "a streak of vindictiveness" and at one point berated O'Farrell for leaving out the 34-year-old Charlton and criticised him for playing Martin Buchan, one of the new manager's signings.

"A lot of the senior players had a close relationship with Matt, even playing golf with him, and they'd take their gripes to him," O'Farrell says. "I suspect he would be saying he would have done things differently. Matt questioned my decisions and created discontent. He wasn't the manager, but he couldn't let go."

The point is relevant because Ferguson has said that after he steps down as manager, he will stay at Old Trafford in a new role. What that will be is not clear, but a boardroom position is possible. O'Farrell has said that would be a mistake. "What happened once could happen again. Sir Alex will find it almost impossible to remain a part of the club and resist still being a counsellor and guru to his old players."

This is not a subject the man himself is willing to debate at length. Ferguson does not like to talk about retirement, and tends to greet questions on the subject with one of those stares that can make you feel as though you have sawdust in your mouth. When it is unavoidable, like this week, he will shift awkwardly in his seat, like a pools winner who has forgotten to tick the no-publicity box.

At his press conference this week the first question about his anniversary was met by his stock rebuttal: "I'm nae getting into that." Later, his position relaxed and, as he reminisced on the last quarter of a century, the 37 trophies and some of the lead performers – "Robson, Whiteside, McClair, Hughes, Ince, Keane – God – Cantona. What a collection" – before enthusing about the new generation, we were reminded of the fundamental reason why he does not want to contemplate a future without football.

Football is the thing that makes the most sense of his life. Twenty-five years at Manchester United? "It's a fairytale," Ferguson said.

And retirement? "All I can say is that I'm looking forward to the next 25 years."